From Data to Aesthetics: A Comprehensive Analysis of Word Clouds as a Text Visualization Paradigm

Preface: From Data to Aesthetics—An Overview of Word Clouds as a Text Visualization Paradigm

In the digital age of information explosion, textual data has become a key resource for understanding social dynamics and intellectual trends. Among the many visualization tools designed to reveal the underlying structure of texts, "word clouds" stand out with their intuitive and aesthetically pleasing form, widely applied in news dissemination, market analysis, education, and academic research. However, is the popularity of word clouds merely a product of modern computer technology? Behind their core encoding logic of "word frequency," might there be an older, more humanistic practice of text visualization?

This report aims to systematically trace the modern development of word clouds at an academic depth, critically examining their technical principles and application limitations. More importantly, this study transcends the boundaries of modern technology, crossing temporal and media boundaries to propose a unique thesis: certain visual emphasis practices in ancient calligraphic artworks and manuscripts from both East and West can be viewed as forms of "proto-word clouds." By creating a dialogue between modern data visualization tools and ancient text art, this report seeks to reveal the common thinking across different historical periods in encoding abstract concepts through visual means, providing new theoretical perspectives and research directions for interdisciplinary studies between data science and the humanities.

Chapter 1: "Proto-Word Cloud" Visualization Practices in Ancient Text Art

The core argument of this chapter is: although ancient times lacked the modern concept of "word frequency," the practice of "visual emphasis" in ancient text art is highly consistent with the principle of word clouds encoding information importance through visual means. We define this practice as a form of "proto-word cloud." Our comparison goes beyond simple word frequency, focusing on three core dimensions: 1) Visual emphasis methods (character form, ink color, size, decoration, etc.), 2) Encoding purpose (conveying emotion, hierarchy, importance, sacredness, etc.), 3) Creative subject and information transmission mode (personal emotional expression vs. objective data presentation).

1.1 "Emotional Word Clouds" in Chinese Calligraphy

Chinese calligraphy, as a unique "art of lines," emphasizes "heart painting" in its aesthetic spirit. It closely connects the act of writing with the inner world, character cultivation, and emotional experience of the writer. This externalization of inner spirit is achieved through a series of non-semantic visual means: the weight and speed of brushstrokes, the density and dryness of ink, variations in character size, and the "momentum" of compositional structure. These elements together form a visual narrative that transcends the literal meaning of words, giving concrete form to abstract emotions and spirit.

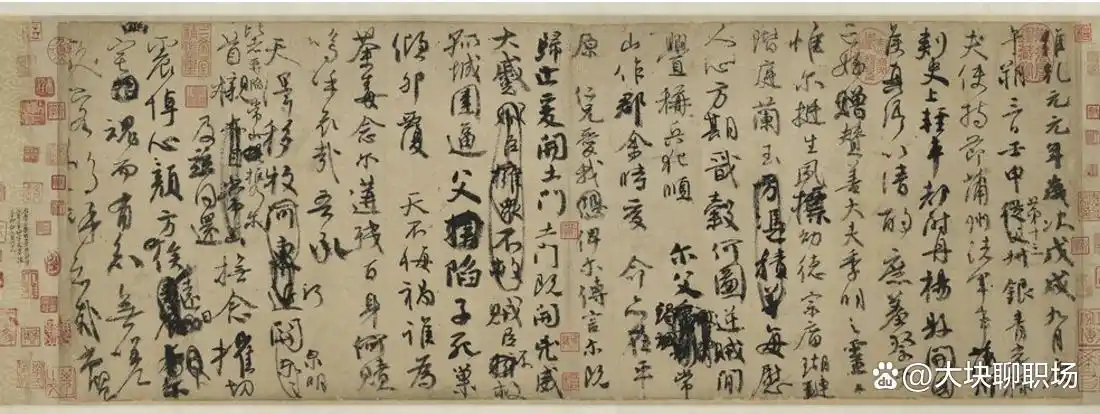

An outstanding example that best embodies this "emotional word cloud" practice is Yan Zhenqing's "Memorial for My Nephew" from the Tang Dynasty. This work is not a deliberately crafted "calligraphic piece," but rather a draft memorial written by Yan Zhenqing in a state of "extreme grief and anger" after his relatives were killed by rebel forces. Under the tremendous emotional impact, Yan "could not care about the refinement of brush and ink," letting his brush follow his emotions, resulting in characters of varying sizes, strokes of different thicknesses, ink marks both dry and wet, and even smudges and corrections. This "chaotic" visual form perfectly corresponds to the heart-wrenching grief carried by the words.

The visual emphasis methods in "Memorial for My Nephew" share remarkable similarities with modern word clouds. Modern word clouds use size to encode word frequency—"the higher the frequency, the greater the importance." "Memorial for My Nephew" uses variations in character form, ink color, and brushstrokes to encode "emotional intensity"—"the stronger the emotional impact, the more dramatic the character variations and ink color contrasts." Its disorder and strong contrasts serve to convey a "trans-calligraphic" grief and anger that transcends conventional norms. This demonstrates that visualization itself is not limited to quantitative data; it is an ancient and universal way of thinking aimed at making abstract concepts tangible and perceptible. "Memorial for My Nephew" provides a concrete visual expression of "emotion"—unstructured and unquantifiable information—offering inspiration for future visualization design: beyond quantitative data, how can deeper humanistic information such as emotions, tone, and even the "intent" behind texts be encoded into visual maps through visual means to create more insightful tools?

1.2 "Hierarchical Word Clouds" in Western Medieval Manuscripts

Unlike Chinese calligraphy, which emphasizes personal emotional expression, Western medieval text visual emphasis practices served more to support religious authority and textual hierarchy. The two most representative techniques are Rubrication and Illumination.

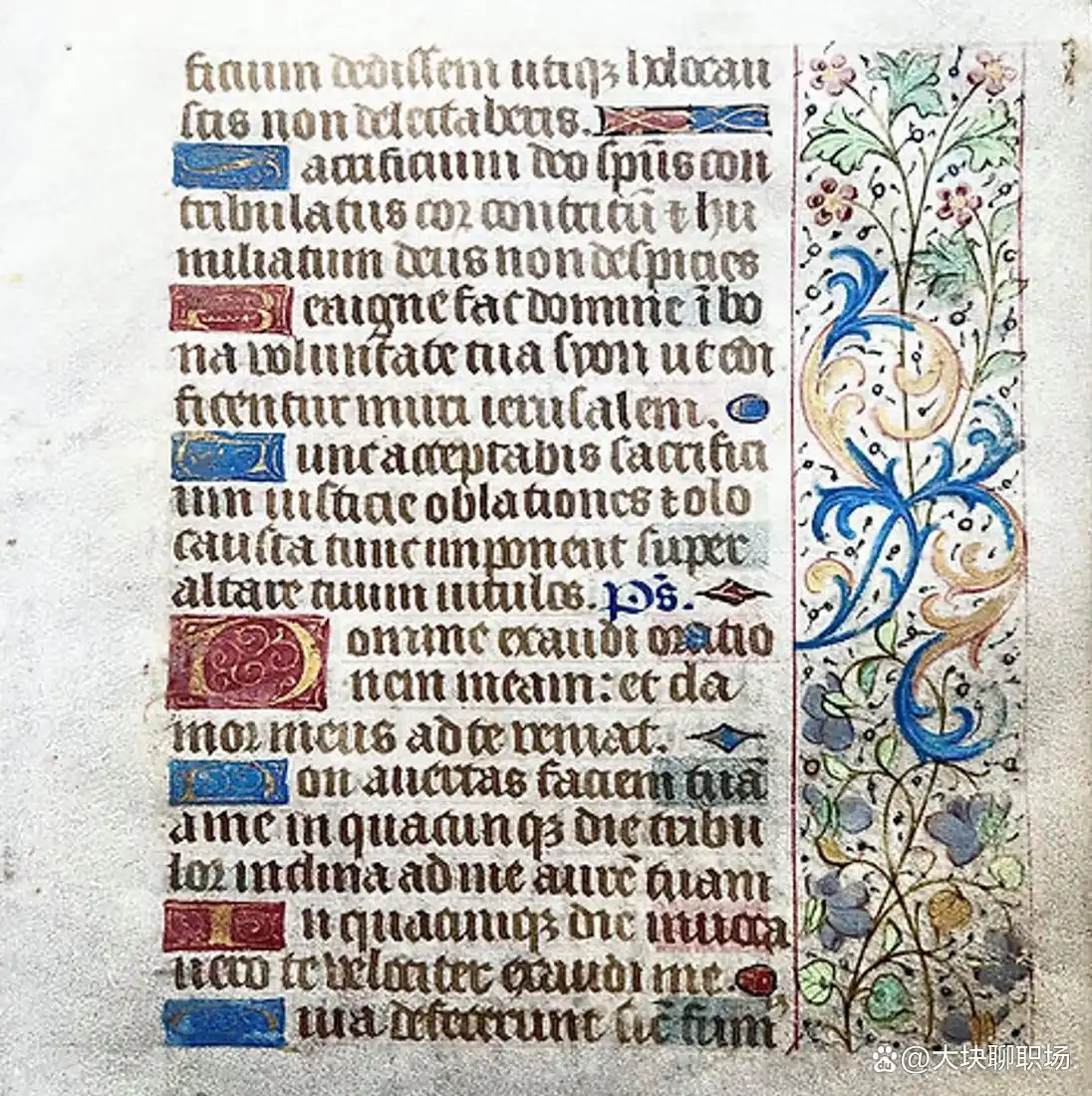

Rubrication is a relatively basic text visual emphasis method, with a history traceable to ancient Egypt. It uses red ink to highlight titles, chapters, or new sections of narrative, aiming to establish the "visual hierarchy" and importance of text. This practice is particularly common in religious books, where red text is often used to mark important prayers or ritual guidelines, while the main text is written in black ink. This is a simple color-based encoding aimed at clarifying text structure, functioning similarly to how modern word clouds distinguish word categories through color.

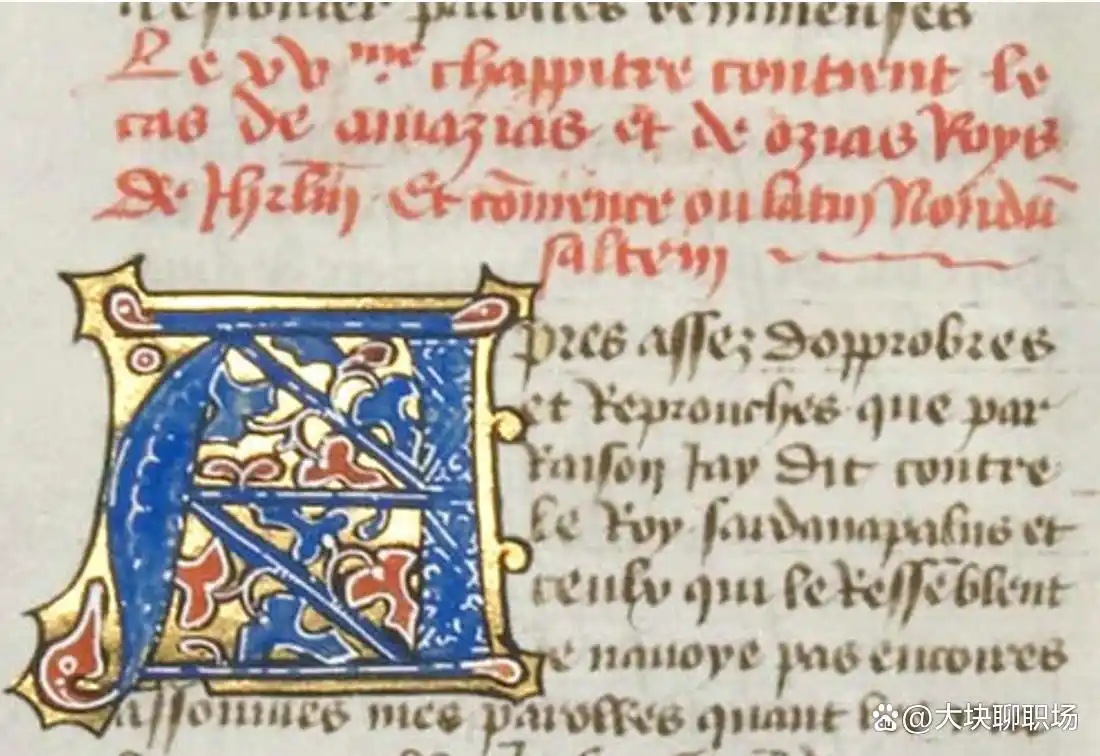

Illumination is a more complex and expensive art form used to decorate the initial letters, borders, and illustrations of manuscripts. It typically uses gold leaf and various pigments, a process requiring high skill and expensive materials. These decorative elements are not optional; they are integral parts of the text, enhancing its authority and sacredness through artistic form.

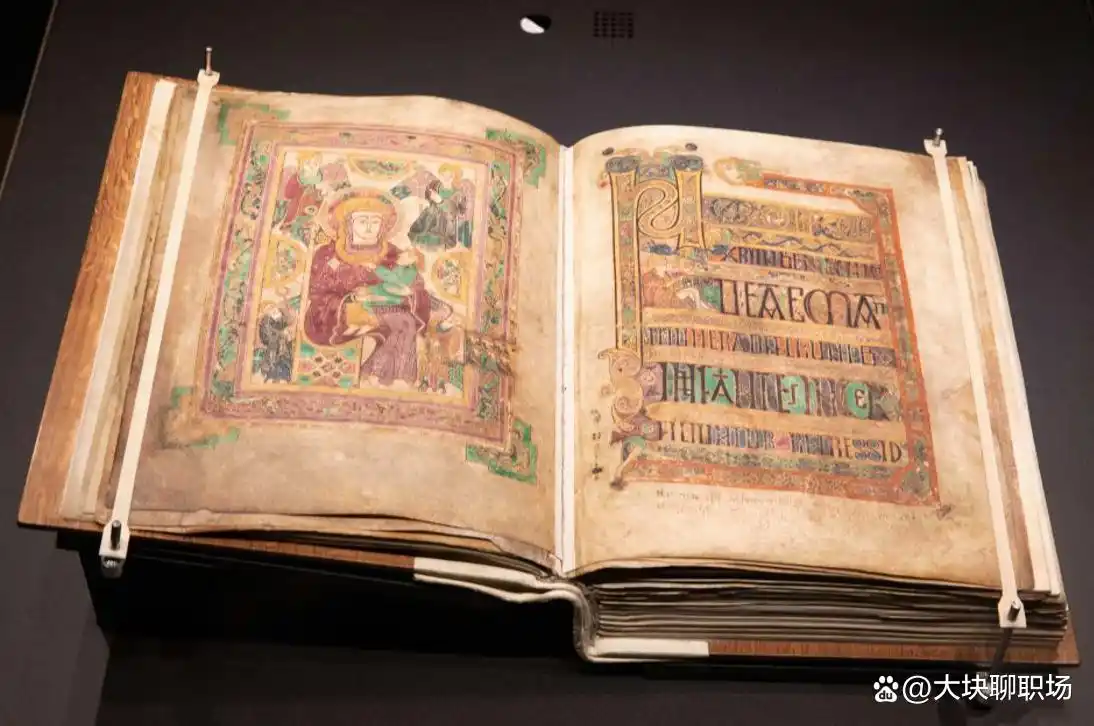

Taking The Book of Kells and Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry as examples, we can see this "hierarchical word cloud" practice.

The Book of Kells is renowned for its extremely luxurious decorative initial letters. For example, the initial letters at the beginning of the Gospels are highly abstracted and artisticized, even intentionally "hidden" within complex Celtic knots and patterns. These decorative patterns themselves carry profound religious symbolic meanings, embedding additional narratives visually, making the text a multi-layered information carrier. This manuscript, through extreme visual complexity, requires readers to be "focused" and "spiritually engaged" before reading, thereby perceiving the depth and sacredness of its content.

Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry is famous for its calendar pages and miniature illustrations. These illustrations, with extraordinary artistic skill, depict the lives of nobles and peasants, adding magnificent backgrounds to the text. The commonality between this practice and modern word clouds lies in their use of visual means to assign "weight" to specific parts of the text. Rubrication is like a simple word cloud, using a single color to highlight importance; while The Book of Kells and Très Riches Heures are like highly customized word clouds with complex aesthetic and symbolic systems, they not only emphasize importance but also embed additional symbols and narratives visually.

This historical context reveals the underlying social and cultural driving forces behind visualization tools. Ancient visualization served authority and faith, while modern visualization serves more for efficiency and insight. But they all follow a common principle: endowing text with new layers of meaning through visual encoding.

Chapter 2: The Modern Journey of Word Clouds: Technology, Applications, and Critique

2.1 Conceptual Origins and Technical Foundations

Although word clouds are now widely known, their technical origins and development were not achieved overnight. Early "Word storms" technology was used for document comparison, with its algorithm core being the arrangement of words by solving optimization equations, but it had a key flaw: the final displayed word sizes might not fully reflect the actual word frequency in the text. This differs from the principle of modern word clouds intuitively reflecting word frequency through font size. From a broader academic perspective, the theoretical foundation of text visualization can be traced back to the "mental map" concept proposed by Milgram and Jodelet, which laid the theoretical foundation for word clouds as a visual tool.

2.2 Word Cloud Generation Algorithms

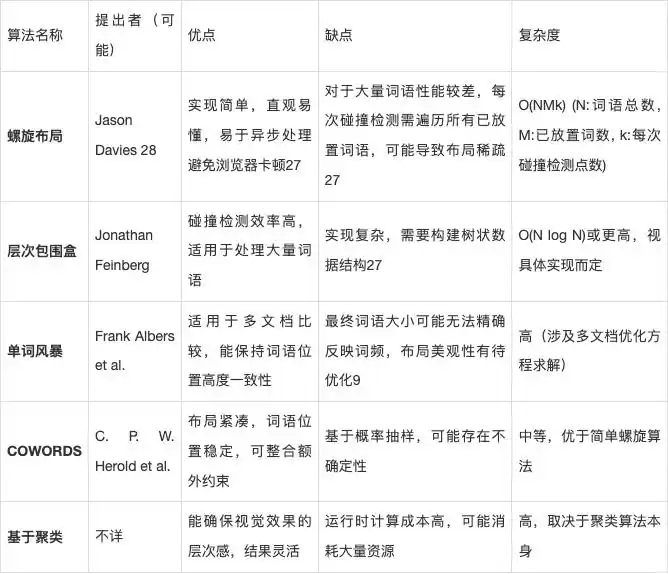

2.2.1 Technical Approaches and Principles

The visual presentation of word clouds relies on complex layout algorithms behind them, which aim to efficiently arrange words of varying sizes within a limited two-dimensional space while avoiding overlap and minimizing blank areas. Different algorithms have their own emphasis on performance, layout aesthetics, and specific application scenarios.

- Spiral-Based Layout: This is the most intuitive and commonly used method. The algorithm starts with the most important word (usually the one with the highest frequency) and attempts to place it at the center of the canvas. If overlap occurs with other already placed words, the algorithm moves the word outward along a spiral path step by step until it finds a non-overlapping position. This method is simple and effective, and can avoid browser lag during generation through asynchronous processing.

- Hierarchical Bounding Boxes and Quadtrees: To improve efficiency, more complex algorithms have been proposed. For example, the famous online word cloud generation tool Wordle uses a combination of hierarchical bounding boxes and quadtrees to accelerate collision detection. This method creates geometric bounding boxes for words and builds a tree structure to manage space, allowing faster exclusion of impossible areas when searching for non-overlapping positions than checking all words one by one.

2.3 Evolution: From Technical Tool to Popular Cultural Phenomenon

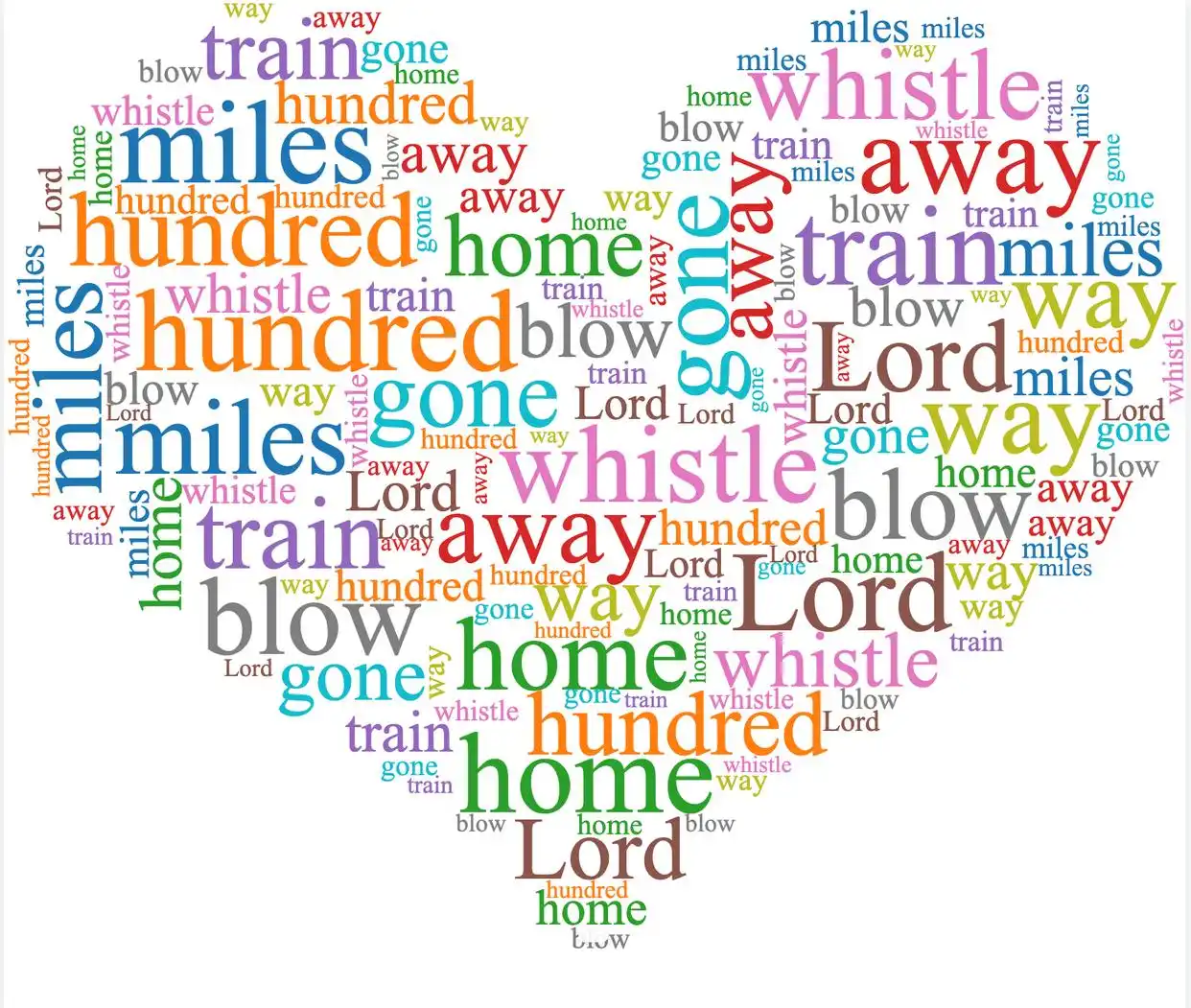

The modern history of word clouds can be traced back to the early 21st century, when they emerged as "tag clouds" on Web 2.0 websites and blogs. Initially, tag clouds were mainly used to visualize website content metadata and served as navigation aids, widely applied on image-sharing sites like Flickr, helping users quickly browse and search content. This early application emphasized functionality—serving as an indexing and navigation tool to improve information system retrieval efficiency.

However, word clouds truly became popular and entered the public consciousness after Jonathan Feinberg launched the online tool Wordle in 2008. After Wordle's release, it quickly sparked a trend in the blogosphere, education, and news media. People used it to analyze speeches, poetry, news reports, and even personal diaries to quickly capture the core themes of texts. Wordle's success lies in simplifying the complex data analysis process into an intuitive, fun, and artistic experience.

2.4 Diverse Application Fields

- Business and Sentiment Analysis: In the business field, word clouds are widely used for market research and customer sentiment analysis. By analyzing massive amounts of customer reviews or feedback, companies can quickly identify the most frequently mentioned product features, service issues, or concerns, thereby gaining actionable insights.

- News and Media: Word clouds have become an important visualization tool for data journalism. They transform complex textual data into easily understandable and eye-catching visual images, enhancing content appeal and information density.

- Digital Humanities Research: The application of word clouds in the humanities has revolutionized traditional research methods. It enables researchers to perform "distant reading" on massive text corpora, quickly grasping macro creative overviews, complementing the traditional humanities research paradigm of "close reading" focused on individual texts.

2.5 Academic Scrutiny: Limitations and Shortcomings of Word Clouds

Although word clouds excel in communication and exploratory analysis, academia holds a cautious attitude toward their value as rigorous analytical tools. Their core limitations are: First, word clouds visualize based on independent word frequency, completely ignoring word semantics and context. For example, they cannot recognize the relationship between "GP" (general practitioner) and "GPs," nor understand the different meanings of "Practice" and "practice" in different contexts. Second, word clouds fragment the relationships between words, unable to present the complex meanings contained in syntactic structures and word combinations. A word may occupy the visual center due to high frequency, but this does not mean its importance in the text equals a low-frequency phrase that can summarize the main theme. Third, visual effects themselves may be misleading. For example, a longer word may appear more important than a shorter word even with the same font size due to its shape and surrounding white space.

Therefore, academia generally believes that word clouds are more suitable as a "starting point" or "screening tool" for preliminary exploration and theme identification of large text data, rather than for drawing explanatory conclusions. The visual appeal of word clouds makes them popular with the public, but their inherent limitations (ignoring context and semantics) make them questioned in academia and serious analysis. This contradiction stems from their design goal: they aim to quickly convey an "impression" rather than a rigorous "explanation."

Chapter 3: Comparison and Insights: Inheritance and Divergence from Ancient Art to Modern Tools

3.1 Dialogue and Comparison

Through systematic comparison of ancient "proto-word cloud" practices and modern word clouds, this report reveals the inheritance and divergence in form and function between the two.

3.2 Philosophical and Aesthetic Insights

Through the above comparison, we can see that the boundary between data visualization and art is not clear-cut but increasingly blurred. From Florence Nightingale's use of visualization for public health advocacy in the 19th century, to W.E.B. Du Bois's use of charts to speak for social justice in the 20th century, to the artisticization of modern word clouds, we find that both "art" and "visualization" are rooted in the deep human need to give concrete form to abstract concepts.

While pursuing functionality, modern word clouds inadvertently echo the disorder and beauty of ancient art. When Wordle adopts irregular arrangements and color combinations, it is borrowing a beauty derived from nature or emotion, which resonates with the spontaneous composition formed by Yan Zhenqing's emotional fluctuations in "Memorial for My Nephew." This comparison also prompts us to re-examine the informational attributes of ancient art. Calligraphy and manuscripts are not just pure artworks; they are also efficient information encoding systems that solved the problems of text understanding and emotional communication through visualization in an era lacking modern technological means.

This understanding will have profound implications for future visualization design. Future visualization tools may no longer merely pursue efficiency and objectivity but will attempt to incorporate more humanistic, emotional, and aesthetic elements, creating "information artworks" that can both provide data insights and touch the heart.

Conclusion and Future Prospects

Through rigorous literature review and interdisciplinary comparison, this report systematically expounds on the modern journey and critical thinking of word clouds as a text visualization paradigm. We further argue that visual emphasis practices in ancient text art from both East and West, especially Chinese calligraphy and Western medieval manuscripts, can be viewed as early forms of "proto-word clouds." This comparison reveals the inherent inheritance in visual information encoding across ancient and modern times—both attempt to endow text content with new layers of meaning through non-semantic visual means.

Based on the findings of this study, the following prospects are proposed for future research:

- Technical Level: Future word cloud research should focus on solving their inherent limitations, such as achieving deep understanding of semantics and context through combining multimodal data analysis or developing new interactive models. At the same time, more precise word segmentation and semantic analysis algorithms should be developed for the characteristics of different languages to enhance the analytical value of word clouds.

- Humanistic Level: Drawing on the visual encoding methods of emotions, symbols, and narratives in ancient art, explore how to develop "emotional word clouds" or "narrative word clouds" that can present the deep emotions, tone, and authorial intent of texts. This requires researchers to transcend the constraints of quantitative data and integrate qualitative analysis from the humanities into the design of visualization tools.

- Interdisciplinary Research: Encourage more cross-disciplinary research in digital humanities, art history, and data science to jointly construct a new paradigm of text visualization that integrates ancient and modern, connecting art and science. Through this dialogue, we can not only better understand the wisdom of the ancients but also inject deeper humanistic foundations into modern information design.